In Rwanda, they count lives in skulls. Each chalky gray orb is a person, a Yorick to some Hamlet who, alas, knew him.

They count lives in femurs too, at a rate of one to two. Each pair is a man, woman or child who used to kick a football, walk to school or run from danger

Each pelvis is a life as well, a person who danced, made love or bore children. The bones, the scaffolding that supports tired flesh, are all that remain of 800,000 people. The hearts that pumped blood, that kept the steady rhythm of life, are gone. The brains that mastered algebra or planned the harvest are gone. All that remains are the piles of bones—in memorials, in mass graves, in farmers’ fields. Like the fossils of dinosaurs, they are reminders of life driven from this good Earth, scientific proof that something ghastly transpired.

The power of the memorials to the victims of the Rwanda genocide is that, save for the genocide museum in Kigali, they are not museums or monuments—they are crime scenes. When I visited Auschwitz on a sunny July day, it was possible, to mistake the death camp for the military barracks it once was. Even the crematoria, if one did not know what they had once been used for, could have seemed innocent. Only the careful collection of eyeglasses and hair and the films of starving Jewish victims crammed into the barracks showed the grim reality of the place.

This is not the case in Rwanda. The sites of massacres look like there were massacres there. In Nyamata, a tidy town 35km from Kigali, there is a church where genocidaires murdered 10,000 people. One knows this not because of archival footage, photographs, documentation or even survivor testimony, but because the victims are there. Their skulls, their bones are neatly sorted and laid on musty shelves in the catacombs beneath the church. In the sanctuary, tattered, blood splattered clothes carpet the floor, proof that these are not the bones of people who died, but of people who were murdered, regular people who had sought sanctuary in a church.

Above it all stands a statute of the Virgin Mary, right where she was when she witnessed the massacre. Her mouth cannot scream, her eyes cannot cry but surely, if she is the mother of God, her heart must be bleeding,

A few kilometers back toward Kigali, the village of Ntarama, another crime scene, tells the same story. The Hutu genocidaires threw a grenade into the local church before coming in with the machetes and slaughtering 5,000 souls. In an annex to the church, the wall is still stained with the blood of a baby thrown against by a genocidaire who treated him like a sickly chick to be culled.

I had had enough. As I drove through the countryside, everywhere white banners with purple writing noted a genocide memorial, but I did not want to visit them. Neither macabre curiosity nor my sense of obligation to the victims could compel me. I did not need to visit the school where not only the skulls, but the bodies of victims remain, mummified by lime, as the ultimate evidence of the crime.

If one travels through Rwanda today without knowledge of its grim history and oblivious to the signs marking genocide memorials, it would be shocking to learn that the country had been the site of one of history’s greatest crimes. Of the 15 African countries I have visited a list that includes continental powerhouses South Africa and Egypt, Rwanda is by far the most orderly. Rwanda’s main roads are neatly paved and traffic laws are widely observed. Even in the provinces, motorcycle taxis will only take one passenger and both driver and passenger always wear helmets, as is required by law. Even stranger, the Toyota minibus taxis, ubiquitous throughout sub-Saharan Africa adhere strictly to the law that they may not carry more than 18 passengers. Elsewhere in Africa, if such laws exist, they police enforce them only to the extent that they are useful in gathering bribes. In Uganda, for example, squeezing 25 people into a minibus is common.

Rwanda’s obsession with order extends beyond traffic to environmentalism. In a highly publicized move, Rwanda banned plastic bags, a major source of litter in Africa, going so far as to inspect visitors at the border for the polyurethane contraband.

Paul Kagame’s Republic even has mandatory community service. On the last Saturday of every month, all business in the country screeches to a halt from eight to 11 in the morning for Umuganda. Even public transportation stops as the Rwandans pour into the streets to clean up their communities.

The combined result of these and other state policies is a country that is safe, clean and remarkably orderly, in the heart of a continent where disorder, if not chaos, is the norm. So how did orderly Rwanda, of all places in Africa, become a place where lives are counted in skulls? I do not know what Rwanda was like before the genocide, but President Paul Kagame’s success in imposing law on his country in a continent where law is as often as not, nothing more than a tool for extortion, makes me wonder if there is something in the Rwandan culture, that imbues its people with a profound respect for authority. Perhaps this respect for authority can serve the good, as people obey the law, but also the bad, as the same people unquestioningly obey the mad orders of a genocidal state?

As a counterfactual, I considered the example of Uganda. Uganda had its own near genocides, Idi Amin took 300,000 lives and Milton Obote another 100,000, but in both cases, the character of the killings was fundamentally different from the Rwandan genocide. In Uganda, the massacres were exercises of military power—ascendant ethnic groups used military might to exterminate their enemies. Civilians were not a major element of the death squads. In Rwanda, by contrast, much of Hutu society was mobilized in the killings. It was as much a civilian genocide as a military operation.

Perhaps it is not a coincidence that Rwanda and Germany, two countries where deference to authority is, or at least was, built into the national character are the settings for two genocides?

I asked Ignatius, my Muganda friend and traveling companion, if he could imagine a genocide on that model happening in Uganda.

“I do not think so,” he said. “Even if people hated the other tribes enough, which is possible, I do not think the Ugandan civilian population could be organized enough to do something like this. Maybe some people would participate, but most, would not. Even, I think, some who would want to kill would not have the organization to do what they planned. They would not manage to show up.”

In a way, it is a sick joke. The lateness, the disdain for authority, and the culture of bending rules that sometimes makes Uganda an infuriating place to live, may also provide a sort of protection against the worst possible outcome. A government that cannot make the trains run on time, may also struggle to make the death squads run on time. But in Rwanda, a country whose organization evokes the West, they have duplicated the greatest sins of Western civilization. Not only can they pave roads like us, they can kill like us.

But this is just a theory, the desperate attempts of one observer to explain what he cannot possibly understand. I want to understand the genocide, to grasp its intellectual foundations because then I can explain it away; I can explain how a unique set of historical and social circumstances turned average people into killers and their country into a slaughterhouse. But I’m not sure that is possible. A people may be more or less violent, a country more or less chaotic, but those are contributing factors, not the fundamental explanation of the Rwandan genocide or any of the great historical crimes. The underlying explanation, I suspect is that the human animal, despite the moral sense that compels him to do good, is fundamentally weak. The Rwandans, the Germans, all of us, are engaged in a constant struggle against our demons, both personal and historical, against the forces that would turn farmers into killers, and other farmers into piles of bones. What happens in a place like Rwanda or Germany is that the structure we have established to fight our weakness, the rule of law and the rule of conscience are inverted as the state and moral institutions like the church go from being the opponents of human weakness to its exploiters.

It is not a coincidence, that there is no genocide where there is anarchy. Surely there is murder in anarchic societies, perhaps murder on an unimaginable scale, as in Congo, but genocide takes organization, and genocide demands the application of power. Human weakness alone is enough to unleash the horrors of war and murder, but a genocide cannot run on weakness alone, it is the weakness of the individual amplified by the strength of numbers.

The genocide, all genocides are not a violation of a human nature, an exception to the laws of man and God, they are a manipulation of those laws, an always lurking byproduct of civilization.

In Rwanda, as in Germany and Turkey before it, the weakness became powerful, murder became the law, and so they count lives in skulls, and deaths in hundreds of thousands, and still can we really say “Never again” and mean it?

Saturday, August 22

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

2 comments:

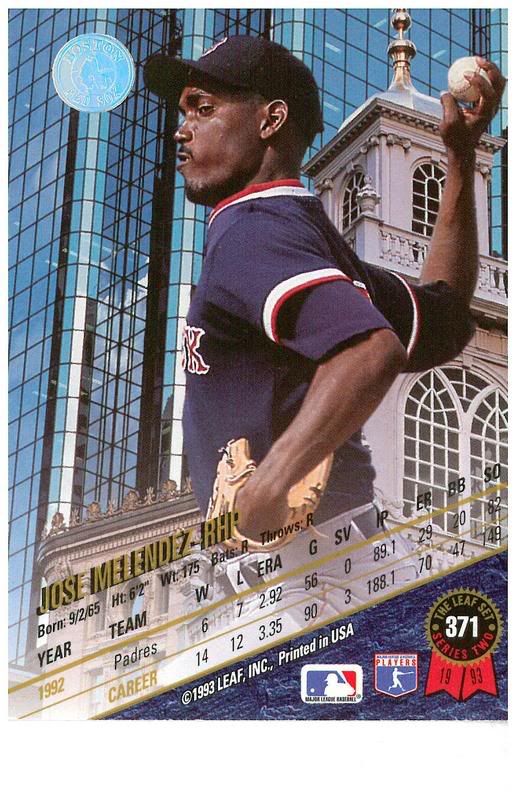

Mr Melendez:

In all these years since the genocide in Rwanda - my country, I was yet to read an article that explained the fast and furious murders of 1994. You give an interesting perspective about the society being very obedient and one that rarely questions authority. I have not been to Rwanda since I was two. Stories from my grandparents taught me everything I know including the language. It is the unimaginable influence from Belgian/French Catholic fathers that instilled this almost over-bearing senseless need to obey without question. The stories from Rwanda are yet to be told and I thank you for opening a small window to the thousands that still ask me today if the genocide in Rwanda is "still happening"! Incredible but true.

Dan,

This was a superb description of genocide, including the anarchy disconnect (no genocide where there is anarchy). Analytical rather than preachy, which makes your conclusions more profound. Maybe in genocide's prevention you have found your calling? And thanks for a great Summer of reading!! Please do us all a couple favors: 1. Become a policy wonk in the Obama Administration (maybe you can be in charge of "Death Panels" since you've studied genocide now?). 2. Please keep writing about whatever it is you choose to pursue. We may need Dan even more than we need Jose (and we really need Jose!). Again, thanks.

PS - In your copious amounts of spare time, check out 'How We Decide,' by Jonah Lehrer (http://www.nytimes.com/2009/03/22/books/review/Johnson-t.html) for a better understanding about what goes on inside a brain faced with decisions, including murder/genocide. Our wiring is a player in all things, good and evil.

Post a Comment