For the next month, Jose is working as a teaching assistant in a class designed to teach international development officials how to do cost-benefit analysis (CBA). The idea behind CBA is that in analyzing a project, one should calculate the total benefit and costs derived from the project over time, and then use a discount rate to account for the time value of money, how one values 10 dollars in a year versus 10 dollars today.

At first it seems quite simple, like all one has to do is project the revenues and expenditures calculate the net present value and rejoice.

But it’s not that easy. In order to do an economic analysis, not just a financial analysis, one must calculate all of the costs and benefits, not just those that are obvious. For example, in the case of a project that causes some pollution, one has to include the cost of pollution in the equation. One must also include the opportunity cost of the project. What is not getting done because this project is going forward? As Professor Robert Conrad put it, “Never let anyone tell you that sitting on a milk crate on your front porch drinking a Pabst Blue Ribbon beer, is not a socially productive activity.”

This endeavor has made Jose wonder if we are really valuing our baseball players correctly. Sure, the Sabermetrics crowd has developed lots of new statistics that measure what players are doing, but is that enough? What about what players aren’t doing? There are some statistics that have captured assess some of the things players don’t do, such as making outs, but Jose knows that isn’t enough.

For example, with Jacoby Ellsbury replaced by Daniel Nava, we know what we’re missing in terms of actions—we’re losing so many hits, so many stolen bases and so on, but what are the inactions we’re missing? What is the added value of the time in front of the mirror that is opened up because Ellsbury isn’t standing in front of it working on his puppy dog eyes?

We know that with Josh Beckett’s injury we have lost so many strikeouts, innings pitched and so on, but we have also gained valuable hours of our lives that are no longer being squandered watching Beckett wait 20 seconds between each pitch. From the perspective of the total economy, it is possible that Josh Beckett’s injury is a net positive.

CBA can be at its most useful in measuring projects where benefits are relatively clear, such as the construction of a bridge. Thus, Jose hopes that it might be useful in assessing what Jose regards as the Red Sox’s most urgent project need, constructing a bridge to the closer.

Given that Jonathan Papelbon is under contract for two years, Jose regards this as a two-year project. That is not enough. If we have to expend $X in talent and salaries this year and next to build and sustain the bridge, then we must derive enough benefit from that bridge this year and next year (note: at a discount rate of let’s say. 03 because that is the standard in health projects, and health is clearly the biggest issue here) if the project is worth doing. Jose doesn’t see this having a positive net present value. We’re going to have to invest a lot up front to get a benefit that will last a maximum of two years, and even that is speculative. Since the bridge is built to a shaky terminus (note: Papelbon) it seems completely possible that we may not even be able to enjoy the full life of the project. Therefore, if the Red Sox are to invest in a project, investing in the terminus, a closer, seems to be a wiser choice than investing in a bridge to the closer. And that’s if one doesn’t calculate a shadow price that accounts for externalities like pollution. If one includes the noise pollution from the nonsense coming out of Papelbon’s mouth, there’s absolutely no doubt that this bridge project is a dog.

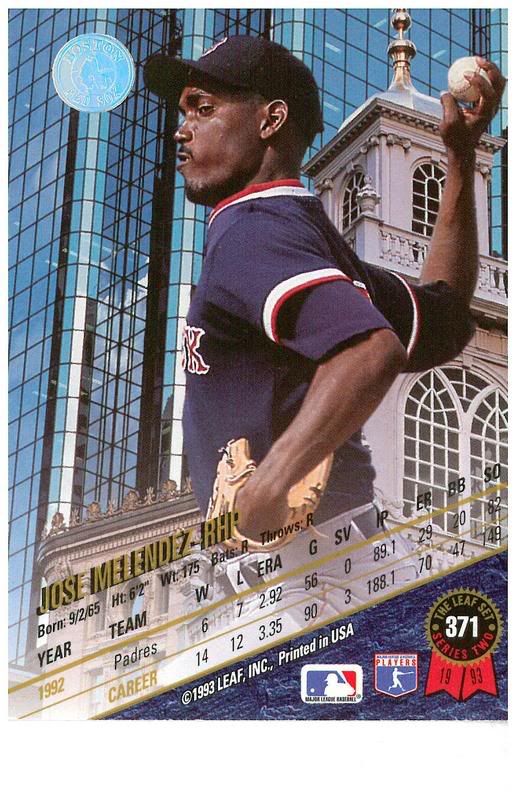

I’m Jose Melendez, and that is my KEY TO THE GAME.